Accelerating Adoption of Water Innovations

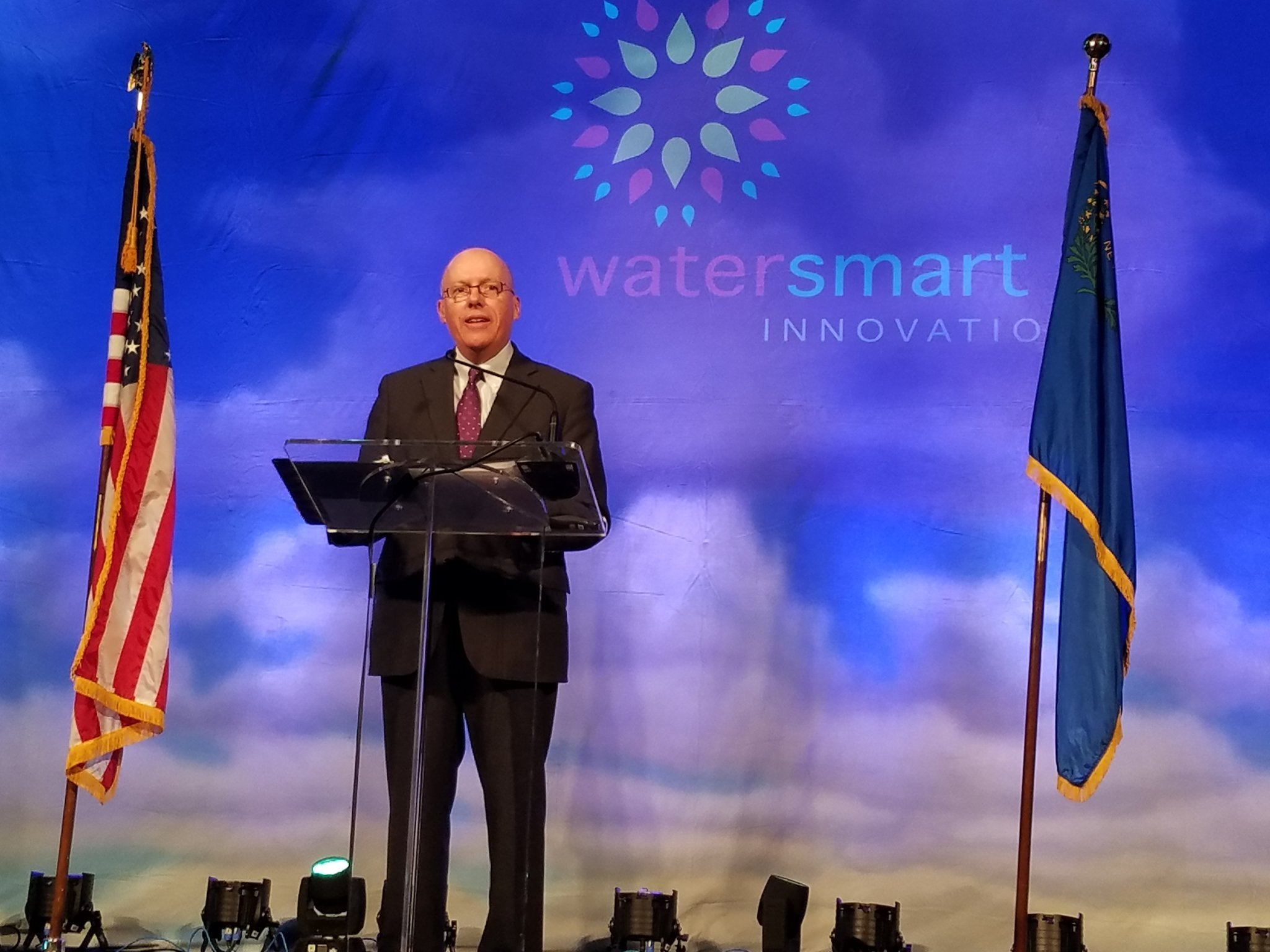

On 5 October 2016, I was honored to present the opening keynote at the WaterSmart Innovations 2016 Conference in Las Vegas. I had been there twice before — in 2010 as an executive at CDM Smith and Chair of IWA’s Cities of the Future Program; and then again in 2013, as a Visiting Professor from the University of South Florida’s Patel College of Global Sustainability. Here’s a brief summary. If you would like to read the entire keynote, you can obtain a copy here. Here is another link to a video of the keynote.

Top-Down and Bottom-Up Innovation

From my perspective, this annual conference brings together the water industry’s most dedicated community of change agents — working enthusiastically to disrupt the status quo. And at the same, it’s a very diverse group of change agents, representing water utilities, technology companies, and NGO’s. Most of participants get very fired-up by the success stories they share at the conference, and maybe occasionally commiserate with one another, when the decision-makers they work with resist learning from, or applying those breakthroughs that have inspired them.

I was looking for a chance to discuss a dilemma that I’ve been thinking about for some time. It stems from having had the experience of working on innovative water projects at vastly different scales — the repurposing of large-scale centralized infrastructure on one hand; and the micro-scale re-invention of urban landscape, stormwater management, and the built environment – one tiny change at a time – on the other.

The questions I posed and answered in the keynote were the following:

Can we span this apparent divide between the large-scale top-down and the micro-scale bottom-up worlds of innovation to arrive at a more unified vision of adaptation and change?

Can we speed up the adoption of both the top-down and the bottom-up simultaneously?

I concluded that the answers were “yes,” but it will require at least three significant changes in how we view water management and the processes that generate and regenerate urban infrastructure.

Competition and the Optimization Trap

The first relates to competition and what I’ll call the “optimization trap.” It involves relaxing an expectation that everything we do must fit neatly into a top-down structure of cost-effective, prioritized, capital planning – resulting in a series of perfectly synchronized investments.

I’m defining optimization trap as the false belief that every solution to a problem can be optimized, and no action should be taken until it has been optimized.

Institutional Barriers to Change

The second relates to standardization, regulations, and other institutional barriers to change. They all derive from important public health and environmental protection goals but can present impediments to innovation in our industry.

We must consider embarking on more innovation initiatives simultaneously, encouraging apparently redundant efforts to accelerate adoption – investing in many real options for a deeply uncertain future.

Re-engagement of Individual Citizens

And finally a less obvious requirement, re-engaging individual citizens in the process – the reconnection of people (including ourselves as water users) to the technologies we have been kept apart from for decades.

The solutions that have the greatest potential of making us sustainable are the ones that re-connect people (all people) with the natural and technological systems that sustain everyone. Not just spectators, free riders on this spaceship, but caring, engaged participants in the real business of living on a blue planet.

Here is a video of the opening session, including great introductions by the conference chair Doug Bennett and Nevada Congresswoman Tina Titus.